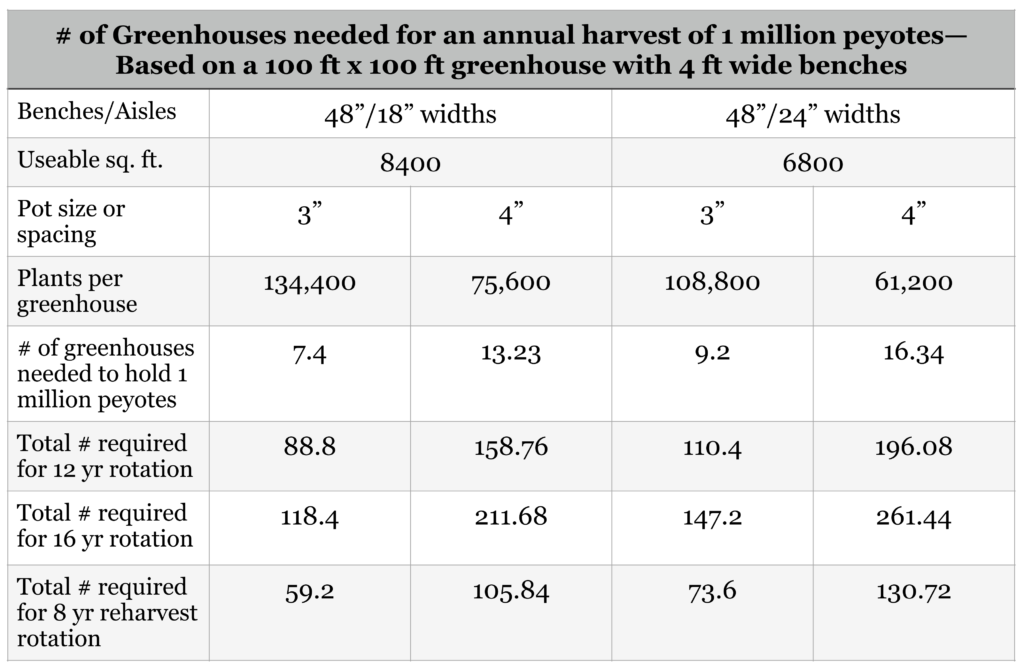

Number of greenhouses required per million peyotes;

with an intended annual harvesting rotation cycle capable of permitting 1 million peyotes to be harvested

This subject involves some large numbers and is easily not accurately grasped due to that. This article was created in hopes of casting some light on what will be involved with a large scale peyote production capable of providing for the needs of the NAC. This ball-parking is for 100 ft. x 100 ft. (30.48 m x 30.48 m) greenhouses producing 1 million peyotes per year once they reach an operational age after 12–16 years.

Numbers are for a 12- or 16-year planting & harvest cycle and an 8-year reharvest cycle. The 8-year rotation cannot begin until after the first 12–16 years have passed.

Obviously 1 million is not enough now so this number will not be enough in the future but this estimation will at least be able to give a sense of the music and provide people with a tool for successfully making those plans. This looks large but we are talking about a lot of plants so relax. It is quite within the realms of possibility to do this; especially if decentralized. And this has been done before but on a grander scale. Even with the longest harvest cycle and the largest size of spacings used in the table below, the total acreage for growing 10 million peyotes would only require around 1% of what is presently enclosed in the greenhouses in Holland.

Downloadable PDF of this table.

The first harvest will not be able to occur until 12–16 years after planting; possibly longer. The re-harvest cycle appears to be 8 years or so but whether the reality is 8, 9 or 10 years will require future empirical evidence. (Our regrowth study intended to provide information enabling sustainable harvesting was poached after 8 years so we could not establish an accurate number, only that it was a number at least equal to or greater than 8 years.)

To apply this to reality:

Multiply numbers above by the numbers of millions that will be needed per year.

Multiply also by the difference in square feet if smaller greenhouses are used. i.e. for 50’x100’ multiply the totals by two. For 25’x50’ multiply by four.

Add 20% for potential losses as it is better to risk abundance than a shortfall.

This does not actually begin with seeds in each of those pots. Losses would be very high. Seedlings are first grown in trays and permitted to enlarge packed closely together until they are large enough to be transplanted into pots. A good size is between 1/2 to 1 inch in diameter (~2 cm).

Cultivation needs to be designed large enough to accommodate the future growth of the NAC as the first harvest that will become available for members will be delayed for 12-16 years after this many greenhouses have been built and planted with peyote. One or two, or even ten, greenhouses are clearly inadequate to fulfill the current or future need. The longer the lag time before starting cultivation on a significant scale, the greater the risk of wild extirpations continuing to spread (with possible wild extinction).

It is extremely promising that two such operations are planned (by ICPI in Texas and SIA in Oklahoma). Their projected sizes and the anticipated dates for peyote production actually coming online are not yet known. While those are welcomed and promising it is also clear they should be supported and encouraged to expand their cultivation operations as much as they have the capacity to manage but even so are going to be inadequate as the numbers in our analysis will illustrate.

To create a cultivation program of a slow growing perennial plant with projections of annual harvests in the future, an equal number of plants need to be planted every year until the operation can become sustainable on a rotating harvest basis. For peyote that cycle may be 12-16 years or it may take longer if the locale is less favorable. Peyote can be grown more quickly though light feeding and heavy watering, or by grafting, but it will be found unsuitable for use as Medicine unless enough additional time is spent under more natural conditions of growth as the mescaline content will be low (alkaloids are plant’s response to stress).

Similarly regrowth is often more numerous but the total weight of the regrowth is much less than the crown that was harvested and this takes some time to catch back up.

This phenomenon of overharvesting creating greater numbers of smaller individuals and any existing harvesting guidelines or best known harvesting practices being ignored in commercial harvesting activity is well known elsewhere and has been reported in fish, ginseng and other natural wild resources [See Terry et al 2011 & Ermakova & Terry 2019]. Similarly the quality of two year old regrowth was found to still be inferior to unharvested crowns but the period needed for their recovery has not been established. [Kalam et al. 2013]

See the details in Kalam, M. et al. 2013. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, 7(1): 435–440. A preliminary report of mescaline concentrations in small regrowth crowns vs. mature crowns of Lophophora williamsii (Cactaceae): Cultural, economic, and conservation implications.

Download as a PDF

The rotation period may be able to become 8 yrs or so once that first period is passed. The exact details remain to be determined and even if the information was available each individual operation will have results that depends on their unique circumstances. These are the present estimates based on the best available information.

Totals will depend on:

1) Size of the greenhouses (and their micro-climate).

2) Size and spacing of benches and aisles–also whether the operation can pull off a multi-tier operation or operates on a standard single level approach.

3) Size of pots or spacing of plants.

4) Number of million plants needed for an annual harvest but projected for the NAC membership of 12-16 years in the future.

Band pots (3”x6” & 4”x8”) are available that will allow deep taproot development with a small footprint. These could help make both harvesting and planting out easier.

Mass harvests of millions of plants per year will require good planning. Whatever numbers are projected as the goal should have 20% added to accommodate death following harvesting or potential losses from unanticipated injury or disease.

Plants can be packed more tightly together but a commercial operation like this needs an eye for the long-term future and factoring in enough space to permit harvests, and future re-harvesting from the long-lived perennial mother plants without adversely affecting subsequent harvests due to incidental damages. (There is no reason to not believe that peyote’s potential lifespan is more than twice that of a human being. )

Even a four-inch spacing will become a challenge if this is performed sustainably. Giving those larger plants more space could be a beneficial option despite reducing the total numbers in a given greenhouse but it may be found advantageous to harden and plant out larger clusters after a period of greenhouse service and keep replacing them with new seedlings.

Spatial consideration of access and spacing is also important to avoid causing harm or repetitive stress injury to the harvesters when performing mass harvests in awkward or tight spaces. Human health and safety should always be regarded as a precious resource to protect in any agricultural operation.

A future challenge will be resisting the temptation to begin using the cultivated plants too soon. This will be counterproductive both in terms of the project and the perceptions of its viability at producing acceptable Medicine. Young or well-watered plants will not be found acceptable by experienced peyote users.

One hurdle concerns NAC members requesting the buttons be cut deep so they will stay fresh longer (accompanied by the claim that they will rot if this is not done; which actually involves HOW they are treating, transporting, storing and drying cut plants rather than the simple fact they were cut properly). Deep cutting is likely to have even greater adverse effects in a greenhouse than in the ground.

Better education on how to cut, transport, handle, store and dry plants appears to be needed. It may be easier to pick apples after the tree has been cut down but that approach limits there being a future.

Repopulation using plants started in a greenhouse and then hardened and replanted back into their natural habitat is valuable but there are two elements of concern. Habitat restoration is valuable not just to help with establishment of the transplants but also to encourage better seedling establishment and survival of the seeds those plants will eventually produce.

The other concern is that physical repopulation using hardened seedlings should be limited to those with genetics appropriate for the locality. Plants from other geographic regions should not have their genetics or soil introduced into a nonnative local environment.

The membership in the NAC was estimated by Prue to be ~500,000 people in 2013, so clearly many greenhouses will be necessary to produce the millions of peyotes needed each year. Prue’s estimate also illuminates there is an unseen volume of unreported peyote consumed by the NAC every year as, according to Texas Department of Public Safety records, the total reported harvest for 2012 and 2013 were 1,106,209 & 1,363,978.

See Prue 2014 (E-published in 2013). The American Journal on Addictions, 23(2): 156–161. Prevalence of Reported Peyote Use 1985–2010; effects of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1994.

The nonlinear claims appearing in the published accounts from 1959—2019 suggest that the actual numbers may not actually be known as the basis for determining them is generally omitted so an analysis of the legitimacy and origin of those numbers is not possible.

See a sampling of those numbers at the end of this commentary.

If we use those numbers, that total volume of reported harvests sold by the distributor could have provided every NAC peyote user with, at most, an average number of around two peyote buttons per year (2.2 per person in 2012, 2.7 in 2013 & 1.74 in 2016). Harvests had dropped to 867,674 by 2016 with the highest reported harvest of 2,317,380 occurring in 1997.

There have commonly been estimated to be more than 70 chapters according to Edward Anderson’s The Divine Cactus. More recently, it has been claimed in Guzmán & Labate 2019 that there are more than 250 NAC organizations in the USA and Canada, many of which hold regular meetings. They cited DPS records as the source of this number but their reference is not available.

Bobby Pedro, roadman of the Northcoast NAC, related to Cactus Conservation Institute that their chapter holds, on average, 55 meetings per year. Common estimates of personal consumption that we have been told by NAC members place the number commonly consumed as being between 8 and 12 buttons per person per meeting although many people only eat four and some eat only one.

Similarly, peyote distributors sometimes slice buttons before drying them; creating more than one peyote button per crown so the reported sales will not always accurately reflect the actual number of peyote crowns harvested and sold by them.

It appears that the NACNA may now have tighter numbers generated in an internal survey concerning volume and frequency of use but the results are considered confidential and are unavailable outside of a quote about DPS estimates of membership appearing in Guzmán & Labate 2019. Moreover, the Texas DPS has now stopped collecting the peyote sales data, so even this source of information is no longer accessible.

The pertinent take-away point to understand from this is that there is far more peyote being harvested from the wild and made available to the NAC outside of what is reported in the sales of the licensed distributors (many independent harvesters exist who leave no records) so a much larger number than they have reported is going to be needed to satisfy the demand of the recognized and authorized peyote using community.

It should be made clear that this is not suggesting some sort of illegal activity is going on here. People with the right to possess peyote were also given the right, as individuals, to harvest peyote, with landowner permission, under Texas’s rules that applied to them, landowners and distributors.

Sustainable harvesting will involve flush cutting rather than angled or deep cutting and will require record keeping and tracking so no that plant is reharvested sooner than 8 or more years after the previous harvest. This will require the cooperation of distributors with each other as one commercial harvester following best practices can easily be defeated by another who does not.

We strongly believe that that best harvesting practices can be effective if properly employed, and they may well have been able to prevent the current state of crisis but it is also clear that implementation of them at this late stage of the game is too late for the majority of known populations that are accessible to harvesters. Opening up more ranches is a short sighted solution.

Two concerns: 1) Harvesting is commonly deliberately deep as was mentioned and 2) There is no existing means of controlling the frequency a given population is harvested from unless the distributors begin to collaborate and share where they collect and when it occurs. Enough time needs to pass between harvests for the harvested plants to actually recover and abundant new growth is typically present long before that point.

The actual numbers of members and frequency/volume of consumption are vital numbers for peyote cultivators to possess as it will not be possible to effectively plan for future peyote production without knowing how much peyote is actually needed every year before making plans to produce it.

These factors make any impediment to cultivation a major threat not only to peyote but to the future of the NAC and other peyote people. One such threat is an attempt at banning cultivation in California rather than simply respecting the cultivation provisions that now exist in the CSA. California is the state best suited for large commercial peyote production operations and, if successful, such an action would at least delay implementation of this important activity.

One other reason more cultivation operations are imperative is in the event something occurs to one of the operations such as an unusually hard and prolonged freeze accompanied by power failure or large hail or a tornado or a major pest invasion. That could be the end of the story for quite some time if production of such a slow growing crop was not decentralized. The ideal scenario would be greenhouse operations in the hands of every NAC chapter that was able.

A few of the many published estimates of NAC membership

An article on Frank Takes Gun in a 1959 Time article, 16 February, page 71 claimed that the NAC had 50,000 members.

La Barre 1975 The Peyote Cult, 4th Edition, p. 224 quoted Hon. Yale McFate decision rendered on 26 July 1960 as giving NAC membership as 225,000.

The details of this court decision can be found in the 1961 American Anthropologist pages 1335—1337.

Omer C. Stewart 1987 The Peyote Religion can be found quoted with a wide range of figures as high as 400,000 but in it I have only been able to locate Frank Takes Guns estimating 225,000 during his testimony in 1960 in the case involving Mary Attakai.

Huston Smith 1996, One Nation Under God, estimated 250,000. This same number was also provided by the NAC to researchers at the University of Virginia in 1998 for a project entitled “New Religious Movements”.

250,000 is the most commonly encountered number and can be found presented as a current value in assorted published accounts spanning five decades.

We mentioned earlier that Bob Prue had estimated membership to be be ~500,000 people in 2013. See Prue 2014. The American Journal on Addictions, 23(2): 156–161. Prevalence of Reported Peyote Use 1985–2010. Effects of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1994.

DOI: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12083.x

This was e-published in August 2013.

In 2016, Sandor Ironrope put the number of NAC members at over 300,000.

See https://www.courthousenews.com/native-american-church-uneasy-with-new-influences/

In 2019, Guzmán & Labate commented:

“According to data from the Texas Department of Public Safety, there are more than 250 organizations and around 650 000 members”, citing an unpublished manuscript of Walker, Walker, & Graves, 2015. The peyote research project: A preliminary final report. Walker Research Group LTD.