Lophophora seedlings |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

It

appears to be a ripe time for reevaluating the article entitled "the

Peyote crisis & some suggestions".

This was

variously positioned as Chapter 2 or Chapter 3 in the revisions of the

book Sacred Cacti.

That

chapter, as written, is greatly in need of revision & updating; and

some additional questions being asked about *its* suggestions. Our use

of the word "I" in this article simply means we want to say this with

one voice. Use of the word "we" refers to the reader and ourselves.

This

commentary, as written, is meant to serve the great need for better

accurate public education and has been constructed primarily for

clarity of presentation of the contained material. It has not been

created with the same density of in-line references such as would be

the case for a work that was intended for print publication in a peer

reviewed journal. It is hoped that adequate documentation and

references are included for the benefit of people wanting to learn more

but if YOU want to learn more or need any additional clarification or

supportive documentation please drop an email to keepertrout at gmail

and ask.

Accompanying

this information is the feeling that there is some urgency in it being

released. It is therefore being made available for public inspection

and comment without further delay.

The

plants of tomorrow begin with the seeds that are planted today.

Commentary & thoughts by Keeper Trout, Blake Edwards & Martin Terry

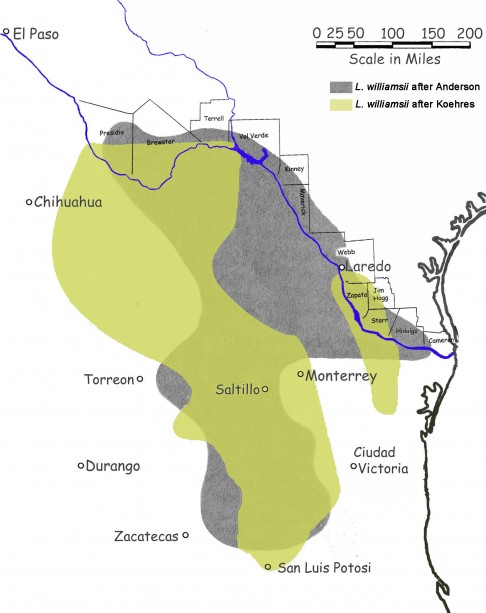

First, concerning the "crisis"....One suggestion, really, is all that is required; assuming that it can be heard, without prejudice, where it matters. Cultivate the Medicine.It is really simple yet that simple truth of the matter has been almost completely buried, if not forgotten or deliberately obscured, in rhetoric that has at times variously been self-serving, manipulative, deceptive, disingenuous, confused, based on misunderstandings, culturally bigoted, or sometimes even entirely delusional. There really was not any delicate way to put that so I apologize for trodding on anyone's conceptual toes. Some people might ask: If peyote is a pressured species, why isn't it cultivated? The question, "why isn't it cultivated?" is a really good one. You and I will be exploring its answers in some detail. We should start by clarifying some things and being certain that we all have a good grasp of an unnecessarily convoluted story. The conservation status of peyotePeyote is most certainly not extinct as some people strangely seem to believe and are even willing to say openly as if it were a fact. It is not yet really even an endangered species as more than a million living peyote crowns were no doubt harvested in South Texas again this past year by the licensed peyote distributors (I have to say probably as the numbers are not yet available). A perception that the pressure from peyote harvesting is endangering the species is nothing new. While it does not appear on any federal listing of endangered species, peyote WAS declared an endangered species by the Texas Organization of Endangered Species (TOES) according to Morgan 1983: 83-84. Despite having a long history of cost sharing with land owners for brush removal and clearing of land, since the late 1970’s the U.S. Soil Conservation Service has refused to do so in any area containing peyote, as the SCS recognizes it to be a potentially endangered member of Texas flora (Morgan 1984: 292). Their lack of financial contribution has not slowed the clearing of land in the development of South Texas. Only recently was peyote actually finally recognized as having adequately dwindling numbers to merit being assigned a status of "vulnerable" and being placed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. [http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/151962/0]. Debates as to whether it should or should not be placed on the Red List had been going back and forth for some years, Oddly, what seems to have tipped the balance of opinion was the appearance of cosmetic/pharmaceutical industry products known as Pomada de Peyote. [Link 1] [Link 2] [Link 3] [Link 4] [Link 5]. I'm not including these links to suggest that any should be patronized but simply to note what came up in a Google search for "pomada de peyote" on 1 November, 2014. Here are images of five of the products that were found to be offered on the first search results page.

It is certain that as both a liniment and an ointment, similar formulations have existed for a very long time at the folk level, and more recently as products of a local cottage industry. These products have likely achieved visibility only when the distribution venue was moved from local yerbarias to online marketing.

One of the companies now producing pomada de peyote is an established business that is substantial in size and has previously developed other successful product lines. The future development of this product will be interesting to watch. It may be noteworthy that the number of different producers showing up as hits on the first Google search result page went from two to five within the past year. Peyote is not endangered as a species for a variety of reasons. The most notable being that there are large expanses of the Mexican peyote populations left. The secondary reason is that not all peyote is accessible for harvest. In some cases, harvests are deterred by a lack of road access but in at least one instance a local population (in Mexico) is protected by the resident humans who interestingly do not use their local peyote for any purposes other than as an external analgesic applied to burns, bruises and aching muscles & joints. In Texas it is a different story. The vast majority of its peyote populations have long since been removed during the course of the modern-day occupation/development of South Texas real estate and the collateral development of its assorted resources. Some peyote finds protection on large ranches with tall fences designed to retain game animals that are hunted for a hefty fee. When the owners of such large tracts of brush also do not permit peyote harvesters to access their land those properties form unintentional peyote reserves. The land that is left as accessible is heavily impacted by the existing peyote trade. In addition, the commercial peyote harvest has been insufficient for meeting NAC needs for some time. There are two distinct but inseparable subtopics within this main topic of the threats to peyote, whether those threats are due to habitat loss or over-harvesting or any of the other known challenges that peyote faces. One is the future of peyote

as a species and the other is the future of the NAC

as a Medicine-based spiritual organization that has both adequate and

uninterrupted access to its Medicine. What has happened to create dwindling peyote populations?Reading the popular press or listening to people talk, one would think that overharvesting by Native Americans or "hippies" is the cause. One or the other or both typically gets the most common and most vocal blame. This is true, despite it being absolutely clear that the vast majority of peyote's obliteration, both in terms of absolute numbers and in total acreage, has actually been the incidental destruction of populations during the process of land conversion. All other factors combined pale by comparison. There have been many reasons for this; the development of land for various projects, such as construction projects, shopping centers, parking lots and tract communities, or as a result of the brush suppression methods that enable ranchers to use their land for agriculture or ranching. Once a piece of land has been converted, peyote does not return.

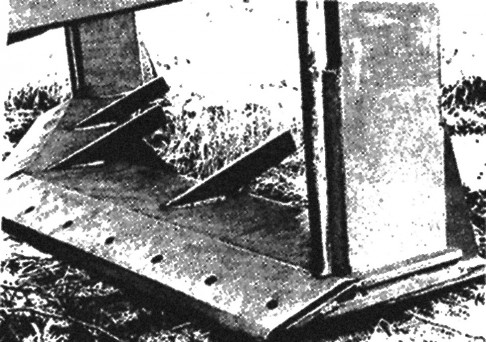

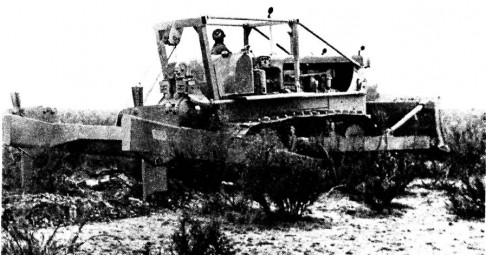

Most of peyote's habitat in South Texas is covered with a tangle of dense thorny brush. To make their land available for agriculture or cattle, it was once a common practice for landowners to root-plow the soil due to the tendency of the thorny brush to come back with an aggressive vigor after being cleared. Root-plowing severs the roots below the soil surface thereby weakening whatever of the roots can't be uprooted and suppressing their ability for good regrowth. Or at least suppressing it for longer than might be the case without it. Repeating the process a few times does help but it is noteworthy that what actually becomes most suppressed is the diversity of life while the actual species that were attempted to be eradicated often go on to become the predominate vegetation.

Root-plowing has been determined to have lasting adverse impacts when used in dry regions. In arid environments with abundant limestone, in this case it is present as a calcareous gravel, rainwater dissolves the carbonates and other soluble ions but there is insufficient volume of water to carry what is dissolved more than a fairly short distance into the earth, accumulating and eventually creating a bed of 'caliche' at the depth of maximum moisture penetration. Due to rainfall being variable in the total amounts delivered per storm, this eventually forms an irregular gradient of alkali concentrations existing between the caliche and the surface ; with the surface obviously being the most life friendly. The layer of decomposing organic materials at or near the surface adds to the ability of the soil to support life. This natural zoning develops over long periods of time with whatever level of moisture they DO have accessible. As it becomes increasingly basic with increasing depth this also means that that the surface is most amenable to supporting life. Accompanying that is the observation that, as rains moved part of the soluble alkali into the earth, that action helps make the surface more life friendly. This fragile balance becomes completely undone with the mixing of the top half meter of soil during root plowing. In this process, the more basic material that has been migrating away from the surface is partially returned to the surface during the mixing process. Recovery is typically slow since the reduction of the alkalinity at the surface level relies on repeated water percolation over time. The resulting increase of surface alkalinity leads to a die-off of small cover plants following seed germination and adds prolonged difficulty in reestablishing the normal flora. In adjacent areas that are used for agriculture due to being more sandy loamy than gravelly, and additionally due to the topography of the land being flatter & less sloping, this creates problems with blowing dust. As a result root-plowing is now discouraged for those soil types and when it becomes needed specialized implements are used to selectively remove single plants. The important thing to understand about root-plowing is that unlike the thorny brush that the root-plowing is intended to eradicate, a single thorough root-plowing will generally permanently exterminate all of the existing peyote on that a given piece of land. If you want to gain a really solid grasp of this technology and a better understanding about why it would impact peyote so adversely, visit http://YouTube.com and search for "root plow" or "rootplowing". Nothing describes the process better than watching a root-plow in action. Other brush-clearing methods are not less destructive to peyote but they do impact the soil and ability of the land to recover less than root-plowing. YouTube can provide looks at modern techniques of "brush clearing in South Texas" as well.

A new threat to peyote in South Texas are windfarms which choose the highest points in the Bordas Escarpment for their placement. These of course need an access road permitting both construction and maintenance. Those roads potentially carve through some of what few undisturbed peyote populations still remain in South Texas. What do we actually know about the harvesting of peyote?Surprisingly little study has been done on the impact of harvesting itself. As far as I am aware, only one organization, a nonprofit group named the Cactus Conservation Institute, has taken the time to learn more despite the immense need for this information as regards both the NAC and peyote conservation. It is clear that the peyote plant is a resilient species or it never could have permitted mass harvests to continue for so many years in the face of diminishing habitat. There are many articles that are available concerning the harvesting of the peyote plant and about its habits and habitat. It IS known that the best way to cut peyote

is at ground level. Cutting too deeply increases mortality and weakens

those plants which do manage to recover. Peyote harvesters often use a shovel with sharpened edge or a machete. Both of those tools can work great for cutting at ground level or they can be mis-employed and produce a deeply angled cut.

What do we know about the impact of peyote harvesting on wild populations?A simple overview:More complete details concerning the items in this list can be gleaned at the Cactus Conservation Institute website or in Kalam et al. 2013, Klein et al. 2015 (in press), Terry et al 2011, 2012, 2013 & 2014. 1) Peyote harvest causes a small increase in mortality. 2) If harvesting is repeated too frequently, this rate of mortality increases. 3) Harvesting also reduces the amount of harvestable biomass of sacrament per plant. 4) The aforementioned observation (3) is initially obscured by the increase in numbers due to the common occurrence of multiple regrowth. However, the sum total biomass of head (crown) tissue per plant, even after 4 years of uninterrupted regrowth, was still significantly smaller than the biomass of the original single head that had been harvested four years before. The study to determine the minimum sustainable recovery period after harvesting is still not complete, but it now clear that the time required for recovery from a single harvesting event is greater than six years. 5) Analysis has also shown that even after four years the regrowth had regained only half the potency of the original crown. It is not yet known how long it takes for the original potency to be re-established in the regrowth buttons. 6) Current and future seed production contributions to the local population are lost along with the harvested plants. The typical fate for peyote seeds following a harvest is into the trash or compost. During the late 1990s, Leo Mercado was able to successfully recover (and plant) many thousands of seeds from the piles of hairs and tufts that accumulated from the peyote cleaned in preparation for a large ceremony. That event, at an annual NAC meeting at Mirando City, consumed more than a thousand crowns. (Information from a personal communication with Leo in 1998.) 7) The oldest and largest plants have been selected for by their environment as those are the plants which are best suited to survive the peak adverse periods of weather. These are commonly preferentially harvested - precluding any future contribution they might have made to the genetics of the population. This last point may be subtle but played out over a long time can become significant. Following the removal of these genetically superior products of natural selection, future adverse periods of weather will likely begin to produce an increased adverse impact on the remaining population.

Peyote plant with multiple regrowthRecoveryLet's go over through that overview again

but this time from a slightly different angle of thought and consider

those factors in terms of recovery.

Recovery is best understood not by looking

at recovery of the individuals which are involved but of the health of

local populations which are composed of many individuals. 1) Replacement of the plants which die as a result of harvesting. (Replacement in this case is being considered only in terms of the natural recruitment of new seedlings although cultivation and wildcrafting would also enter the picture in this area. Wildcrafting is the conscious planting of seeds or return of plants in such locations where the plant might naturally have occurred.) This decrease in survival is thankfully a fairly low rate but it is not insignificant if a field is revisited as each subsequent visit may result in the reharvesting of plants which are still drawing their sustenance from the original reserves of the remaining taproot fragment from their mother and have not yet had time to manage to grow a replacement taproot. The rate of mortality has increased with each time that reharvesting occurred in what limited study of the topic has occurred so mindfulness is needed not just of how deeply a plant is cut but also when it was last cut. Until after the point that a plant can regrow a taproot it is vulnerable to outright death from loss of its photosynthetic tissues as occurs in harvesting. This subtle but simple fact is somehow often either missed or trivialized: when the crown tissue has been removed the peyote plant loses its ability to use the sunlight. This remains true until after a new crown can be made and it reaches the surface of the ground where it can absorb sunlight to once again photosynthesize and feed itself. Repeated cutting too frequently forces the plant to exhaust its limited reserves and interferes with good regrowth and survival. Plants that have been harvested need adequate time to replace their missing storage tissues (by photosynthesis in the crowns of the regrowth pups) before being reharvested or their death rate increases; eventually requiring their actual replacement. 2) Regrowing new crown tissue to replace the harvested crown with its equivalent prior to reharvesting.Even though multiple crowns commonly result following harvesting, it takes some point greater than six years for their combined total weight to match that of the original crown. (The study to determine how long it takes for the sum of the regrowth buttons to equal the weight of the original harvested crown is still ongoing.)Harvesting prior to following that point of recovery will provide smaller and steadily decreasing volumes of harvests. This is a practice which feeds into the spiral towards smaller, weaker plants with higher loss rates. 3) Recovering the original level of alkaloids. After four years the average alkaloid level of new growth was only half that of the original crown. It is presently unknown how long it takes for the preharvest alkaloid level to be restored. Harvesting prior to following that point of potency recovery will provide an inferior quality of harvests, requiring consumers to ingest more plants, which also feeds into the extinction vortex towards smaller, weaker plants with higher loss rates. 4) The population also has to recover from the impact of however many years it would take seeds from those harvested plants to be replaced by new seed-producing crowns, and this must be taken into account if wanting to accurately assess the impact of harvesting. Every plant which is taken means that many less seeds are available for the local population for at least a handful of years. This is not insignificant as wild peyote in nature primarily reproduces via seeds. Removing a plant means removing all future seed contribution by that plant. If older plants are preferentially harvested and as numbers dwindle the age of first harvest also decreases, it rapidly produces a situation where the only plants to harvest may have flowered only once or twice or not at all, creating a huge seed production deficit for the local population. In the event of adverse weather (whether prolonged drought or beyond average freezing) causing an above average loss rate, this adds to the risk that the local population may not recover. I’ll let you, the reader, do the math for yourself.

What about the sustainability of harvesting?Peyote harvesting appears to be a

sustainable practice, at least in potential or in theory. In its present-day application however, the

slow attrition process leading to the endangered species path has

already clearly begun. It is clear that the consumers of peyote still

have plenty of peyote to last for some years to come. Maybe even for

the rest of our lifetimes, especially if you are middle aged like me. Much more study is needed to better define

what was seen in the limited harvesting studies that exist but this is

how it looks at the moment: So, let's come back to our question, "Why ISN'T peyote cultivated?"Probably the single most important element

as to why cultivation is not already a part of the picture is

the simple fact that none of the non-NAC people who are legally

involved in the supply side have actual legal protection permitting

them to cultivate peyote. Whether those are peyote distributors or

ranchers permitting individual NAC members to access their land to

harvest their own peyote, they are in general law-abiding respected

citizens who want to stay out of any trouble. The portion of South Texas where peyote occurs naturally is commonly referred to as the Peyote Gardens, despite there being a complete lack of historical peyote cultivation. There are presently at least two pertinent stumbling blocks preventing this land from actually being used for creating a real peyote garden (or otherwise addressing the fatal long-term flaws that are inherent within the existing distribution system). Those are located within the Texas DPS (Department of Public Safety) regulations concerning peyote harvesting: One for the Distributors: &

Another for the Ranchers has two pertinent features

of interest: Landowners are permited to charge

access fees for peyote harvesting but interestingly there is another

clause in this same regulation that adds: Notice that this is a dysfunctional "one-price-regardless-of-harvest-size" scenario that actually encourages the maximum possible harvesting to occur per visit. Since the law further sets the retail price as being per piece (i.e. per button) and not by weight there is just as much financial motivation to harvest tiny plants as older ones. Increasing difficulty in gaining access adds additional motivation to maximize the harvests recovered on every visit. Many ranchers don't like peyote or peyote

harvesting or peyote people and express a familiar bias directed

against them. A not untypical attitude is Sahagun's 1994 quote of ranch

owner Robert East. "I

don't want them here. That's all there is to it. I think it's a dope

business, that peyote." Morgan 1984

included a similar quote: While that degrading analogy blames the "Indians" there is actually a highly valuable insight if we look at what IS actually real within that notion -- namely, as is also true for a rancher's grazing animals, the NAC is in fact being constrained and provided with its Medicine in a regulated and controlled manner rather than having the freedom to do as they choose. Blaming Native Americans for the, ahem, "over-grazing" problem is about as sound as a rancher blaming their grazing animals for "eating too much" rather than, in this case, correctly recognizing that any "overgrazing" was the direct result of negligent planning, counter-productive activities and incompetent management on the part of the ranch manager. Similarly the fees charged by ranchers for access are high enough to stimulate maximizing the harvesting per visit as well. Johnson has mentioned ranchers' greed raising access costs from what once was a pittance to something more significant. Grant gave a 2000 estimation of it then typically costing $1,500 or $2,000 a month for a peyote lease; which provided a small work crew with access to locate and harvest crowns that were then being sold at the retail level for around $0.15 each. There is no question that the public perception of the peyote trade being profitable contributed to that increase in peyote lease fees. Not everyone shares completely identical motivations. Sahagun 1994 described rancher Rick Walker as being "fed up with trespassers. But he suggested another reason for guarding the peyote gardens on his land. Peyote, he said, may one day become a hot commodity - for ranchers." There is at least one rancher in South Texas, the identity of whom is being withheld, who has discovered a unique way to legally make money from his peyote and still protect them from any harm. Instead of leasing his land for the harvest of peyote buttons, he instead "showcases" his peyote plants. He permits organized "eco-tours" to bring visitors onto his property in a bus as part of a fee-based tour. They are allowed to visit his property under tightly controlled circumstances in order to witness and photograph his healthy population of peyote plants. The tour bus also takes the visitors away at the end of the visit so there is no risk of theft. That population is, just as importantly, also located far enough away from the nearest road to ensure that none of their visitors will be able to return on foot. While this may sound cynical, one other highly significant factor in the perpetuation of the status quo is that the peyote distributors actually derive a very good living from their trade. Despite

the low cost per button, it is actually a moderately lucrative

profession in what is historically an economically depressed region of

Texas since the three remaining peyote distributors combined now

typically report a total sales of a little under a half million dollars

per year ($530,230 in 2013, $434,609 in 2012, $466,590 in 2011,

$459,699 in 2010 and $493,834 in 2009 according to DPS records). This

reflects their combined totals so in reality it is split into uneven

thirds based on how much they actually sell. Each distributor's total

sales pays for their lease fees, their expenses and is also what they

pay to the small group of their 'employees' who help them harvest

peyote. In most cases their employees are their relatives. Sahagun 1994 quoted Johnson as saying,

It is not

a huge amount of money but in a region where relatively few other

alternative options for similarly lucrative employment opportunities

exist it is certainly something that the people involved are going to

care about. While the state law that was mentioned previously as granting the distributors their licensing specifically prohibits the distributors from cultivating peyote, the federal law gives the NAC, or anyone else who is producing peyote for the NAC, the authorization to "manufacture" their Medicine (21 CFR 1307.31). [The regulation says “Any person who manufactures peyote for or distributes peyote to the Native American Church, however, is required to obtain registration annually and to comply with all other requirements of law.” That applies to any person, NAC or otherwise. There is no special restriction to NAC members in this regulation.] Manufacturing a plant obviously requires growing it or else modern technology has become much farther advanced than I am aware. Congress has further added an affirmative clause that suggests NAC cultivation was at least being envisioned as enough of a possibility that its regulation needed inclusion.

Which, at the very least, suggests that the road to the future cultivation of peyote by the NAC appears to be open as an available option that is protected by federal law. As AIRFAA treats cultivation in exactly the same manner as it does distribution, and because regulated distribution requires a long-standing registration process that functions daily before our very eyes, it would seem to be obvious that Congress intended cultivation to be not merely a hypothetical possibility, but a real option that should be realizable by the act of registration (to be defined and regulated, of course, by DEA).

Robledo 2006 included a thought-provoking comment that was left unexplained but touches on an often overlooked contribution to peyote harvesting by the NAC:

In 1988, after interviewing the active licensed distributors, John Morthland commented:

An actual attempt by some peyote distributors to control the peyote trade and deliberately try to prevent cultivation by their customers actually goes back a very long time. Some comments from BIA Special Agent "Pussyfoot" Johnson were featured in an intriguing account by his supervisor that appears in a 1909 issue of the Indian School Journal, entitled "History, Use and Effects of Peyote."

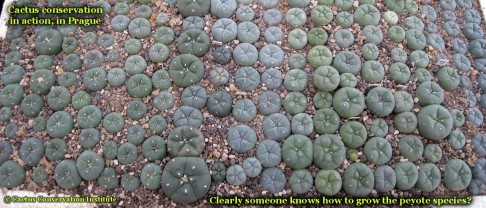

All images © are copyrighted by the photographers and/or the CCI and are used with permission. Reproduction is forbidden without prior written consent. Cactus

Conservation

Institute

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||